What if we go 4–2–2–2 in FM23?

A traditional — yet uncommon — formation nowadays in FM23 (only time I saw a coach using it was Nagelsmann at Bayern when in great disadvantage), the 4–2–2–2 has some advantages that may bring havoc to opponent defences whilst giving defensive sturdiness. The following text is not your common try-this-and-that tactics, but a reflection on how you can properly build a 4–2–2–2 that fits and suits your own team. With a few tweaks and so, it may be very valuable.

=> The 4–2–2–2 box

It’s pretty unorthodox for european coaches to use a 4–2–2–2 narrow, since it gives a good center midfield control, but tends to lack a good defensive approach, especially if one considers the modern trend of using wingers and offensive positional play in a 3–2–5 or 2–3–5. Nevertheless, some teams thrived in playing a more fluid 4–2–2–2, like RB Salzburg with Roger Schmidt — even though it resembled more like a 4–2–4/4–2–4, since the AM played a bit wider, but with inward movements — and Carlo Ancelotti spell at PSG.

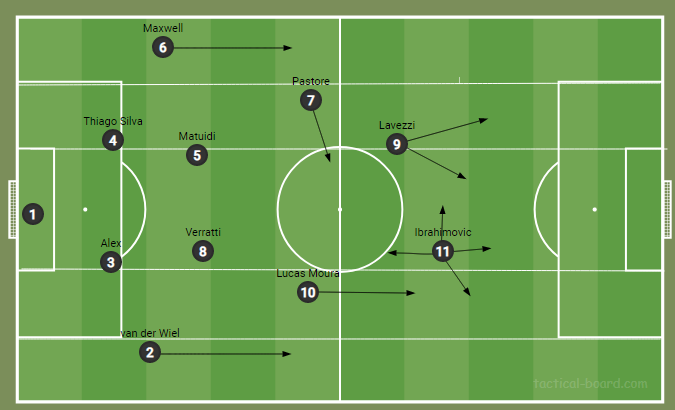

As one can see in the image above, the 4–2–2–2 Ancelotti employed at Parc de Princes had Verratti launching balls and dictating tempo, whilst Blaise Matuidi was employed as a more defensive minded midfielder. Pastore started slightly from the left halfspace, moving inwards, while Lucas Moura would move forward in the right halfspace. Both the full-backs — van der Wiel and Maxwell — would move forward to create width. In defensive phase, Pastore and Lucas moved back and the team defended in 4–4–2, with both attacking midfielders tucked really narrow with the defensive midfielders.

Schmidt’s RB Salzburg would work in a different manner: they wanted the 2 advanced midfielders to recover the ball high, so they would work in a 4–2–2–2 structure in order to gegenpress the opponent. Ramalho, the defender launched lots of long balls towards the strikers — not necessarily to get the first ball, or to find a target man , but— to have numerical superiority in the area as so to recover it.

Finally, there is also a traditional trend — especially in Brazilian football — to use a 4–2–2–2. It can be said that most of the tactical imaginary of brazilian football supporters is permeated by the 4–2–2–2 square structure — even when teams wouldn’t play a proper 4–2–2–2. It can be traced as back as the 1980’s, but using some tactical tweaks that are common in brazilian football that can sound a bit unusual to other football cultures: the main features are the utilization of the diagonals and use of assymetries.

=> Brazilian 4–2–2–2 and Assymetrics

The Sarrià’s tragedy is one of the most common stories in brazilian football: not only because it was a sad loss, but because it meant the end of the line of a team that was expected to contend for the title of the 1982’s World Cup at Spain. Nevertheless, the team’s imaginary of the use of a 4–2–2–2 maintains itself on contemporarity.

The 4–2–2–2 was an uncommon formation even to brazilians, who — before the World Cup — would complain at Telê Santana, the “seleção” coach to put a winger.

— PÕE PONTA, TELÊ (Use a winger, Telê)

Despite it, Telê stuck with a formation that nowadays resemble a lopsided 4–2–3–1. The 4–2–2–2 is accompanied by lots of compensations and offensive football. The most uncommon of it is the diagonal, as seen in the next image.

Leandro would be deployed as a right wing back, Junior on the other side was a left wingback — but he was originally right footed, so he drifted inside lots of times. Toninho Cerezo was a deep lying playmaker, while Falcão was placed a bit higher. Zico and Socrates played centrally, even though Zico was placed a bit more to the right hand side of the pitch. Socrates was deployed more centrally — with freedom to roam and a bit higher than Zico — . Eder was the only “winger”, starting from the left halfchannel, trying to give its team penetration from the left, while also trying to score goals. He would be, then, considered a second striker, while Serginho Chulapa was the number 9, the goalscorer.

There are two things to be noticed here:

- Assymetric starting positions

- Hierarchy of movements — the higher in the midfield, the more freedom of attacking play and movement.

Brazilian football, different from those who romanticize past tries to portrait it, is not made by complete freedom, anarchic movements and roaming, but to a social hierarchy stratification that goes beyond the field. The diagonals are set in a manner to define whose players are going to have more defensive attribution — and therefore less creative freedom— and those who are having the most creative freedom — and therefore demanding those who don’t have it to work defensively for them. Does it mean that Cerezo or Falcao were dull and less creative? No! But it meant that their creativity was less important to team work ethics, since their main task was to find the more creative players forward. Cerezo and Falcao were great players, but in a diagonals context they had the task to provide creative freedom to the other players.

Brazilian football is, then, characterized by some sort of caste-like strata in midfield, where each position in it has a different and more defined role.

- Primeiro Volante — Can be an Anchor-man or a ball winning midfielder

- Segundo volante — Might be a segundo volante in FM23, deeplying playmaker or a regista

- Terceiro-homem de meio campo — Advanced playmaker or enganche

- Meia-armador — Enganche, Trequartista

As of it, one should and might think positionality in brazilian football — especially in the football played in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo — not only in it’s vertical lines (that is left wing — left half space — center of field — right half space — right wing), but also horizontal lines, which is usually a representation of more or less freedom. That is, the closer to the defensive line, the more a “piano-carrier” and less of “piano-player” it is. That means that football in Brazil is also tends to be a microcosm of a segregated society in which there are people bound to work hard as to some more creative and “mastermind” who can make the team thrive through its individualities.

That being said, how one could replicate a 4–2–2–2 in FM23?

=> 4–2–2–2 in the FM23. Lopsided or Symmetric?

One must understand that Fm23 has its limitations as to organizing an assymetric 4–2–2–2, since its positioning is mainly based in horizontal organization. Yet, with some individual tweaks one can find some type of possibility of working in this formation.

If symmetric:

Notice that it is important for the players to have good passing and movement, as so to get the ball into the attacking area, while being defensively consistent. If playing with wing backs, beware that you might need the defensive midfielders to play more defensive roles, like ball winning midfielders, anchorman or even halfback.

If played like the above, notice that might be a midfield gap between attacking midfielders and defensive midfielders. This way, I would adapt the team to play through the wide areas — as so to find the wingbacks — and find underlaps — so they can find the midfielders in more central areas. That means a more narrow approach with short passing is interesting. If you want to play a more direct-long ball approach, you may set it at wider so players can find more long balls from one side of the pitch to another. Even though, it is important to respect the individualities of the attacking midfielder. For instance, an attacking midfielder with a PPM of comes deep to get the ball would probably move lower and next to the defensive midfielders to get the ball and link play with the forwards, attacking midfield and marauding wing-backs.

If playing with fullbacks, one might get a more patient approach, and give more freedom to roam for the defensive midfielders, in order to work the play in the center of the pitch and moving up to link with the attacking midfielders. Yet, one may lack the possibility of stretching play, which must be important to consider. Maybe moving an attacking midfielder or forward to “stay wider” would help. As said, important to consider the specificities of the team.

If assymetric: Things may get a bit more “tweaky” and strange to non-brazilians. If you want to play with 2 AMs, one must be on support and other on attack, while one of the DMs must be in defend and other in support, as so to create a “paralellogram” in midfield. The compensation system must also be respected. For instance, the most defensive midfielder usually is on the side of the most attacking wing back, since his task is usally to cover it.

As in the image above, it creates assymetric positioning and may need tweaks. For instance, it is difficult to replicate the number 11 role. The player may need to be placed on the right wing side, or placed in the CF position at the right and asked in the individual positioning, to “stay wider”. One might ask too, if the right back is too defensive, for the Defensive midfielder on the right to drift or stay wider, as so to not lose the right hand channel in possession. The same can be said by the Terceiro MeioCampista (number 7 in image), who can play inwards, but can also be asked to “run wide with the ball”, as a mezzala would do, to create overload on the left with the left wing back.

That said, there are lots of ways you can play a 4–2–2–2. This piece is more of a trying to create context to different ways you can organize your team in a more “latin american” (as an anthropologist by formation, I hate to generalize such different schools of playing, but it serves the purpose here) or a more “european” context. The choice is yours. Have fun!

Help me continue my work so I can bring more of football to you, guys. Be my Patreon at: https://patreon.com/v_maedhros. Any help is welcome.